Why growth mindset should be a way of life

Ask any sixth-form tutor what the most frustrating point of their year is and they are bound to bring up the Ucas PS (that’s procrastination syndrome, by the way, not personal statement). It’s incredibly frustrating for teachers to see budding biologists and aspiring artists reluctant to put pen to paper for fear of producing something less than perfect.

Or consider the Year 7 girl in floods of tears when she misses out on a major role in the lower school play. Or the Year 9 student who tells you she is “just no good at French” and might as well drop it.

A lack of “grit” and a fear of failure are now very common in our schools.

Yet since Professor Carol Dweck first published Mindset in 2006 and Professor Angela Duckworth published her work on “grit”, we’ve had compelling research and clear language to try and support pupils to be more resilient. So, why are we still so far from seeing results?

Some have argued that the research is flawed. The idea of “growth mindset” has certainly come under heavy fire, but turning mindset theory into practice, and not only into practice but into instinct, is never going to be easy, and neither Dweck nor Duckworth ever claimed it would be. Poor practice inevitably creates poor results, but that does not mean the underpinning research has no value. Certainly, in our school, we believe we have found a path through the noise and that we have a resilience programme, heavily influenced by Dweck in particular, that works.

In 2014, I was lucky enough to attend a conference with Dweck, Professor Barry Hymer, the writer Matthew Syed and a range of speakers from schools beginning to implement growth-mindset initiatives.

I spent the next months reading voraciously: learning about the original research in Mindset, followed by Syed’s wisdom on incremental gains and resilience in his book Bounce (2010) and the importance of feedback and concepts of potential in John Hattie’s Visible Learning (2012).

It seemed to me that students not only needed to understand how adaptable their brains are but also to take part in specific training in how to apply that knowledge.

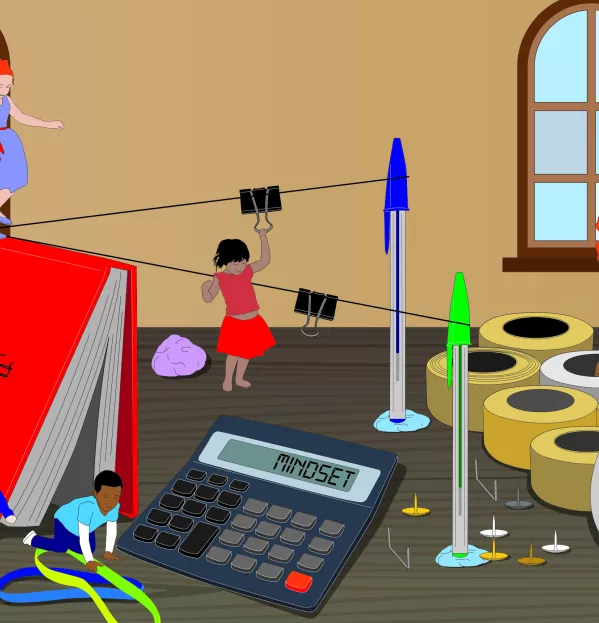

I was given some time to develop a programme in school and meet whole year groups from Year 7 to Year 13 to work on growth mindsets. The aim was to help students and staff understand and apply four key principles, which we expressed in imperatives: “flex, try, feed back, inspire”.

“Flex” is a way of communicating brain plasticity by comparing the brain to a muscle, which can be trained through effort and a degree of overtaxing.

“Try” expresses that it is rational to persist if we believe our brain can adapt so we get better at things; it then makes sense to try different approaches if the first doesn’t work.

“Feed back” is all about being interested in the constant flow of (hopefully constructive) critiques from teachers, parents, peers and the world around us.

“Inspire” encourages us to use other people’s successes as a jumping-off point for our own, by identifying local heroes (my friend, who is a whizz at maths, for example) and consciously emulating aspects of their behaviour.

Year 7s were first up in the programme, with a session on trying new things. Students were presented with mystery challenges in boxes, which ranged from sampling a food they had never eaten before to agreeing to run a year meeting the following week. It is a sad fact that, even at the tender age of 11, students can arrive with rather fixed ideas of what they like and where their skills lie. September of Year 7 is a great time to strip away some of the labelling that can dampen their enthusiasm and restrict their development.

In the second part of the activity, tutors - armed with mini whiteboards to note down some top tips - led group discussions on how we can be inspired by others, and how to break up difficult tasks or skills into small steps in order to improve. At the end of the morning, we all signed up to a 30-day challenge: committing to the daily practice of one of these small steps.

Having looked at “flexing” our brains by taking opportunities, next in our sights were concepts of failure, or how feelings might sabotage our students’ determination to keep on trying.

Year 8s were invited to contribute to a graffiti wall, writing down what they said to themselves when they thought they had failed. Posters were soon filled with scrawled insults: “Loser”, “You’re hopeless”, “You’re stupid”, “You’ll never get this right”. We then watched a video clip of a young American boy, Matt Woodrum, running in a race. Matt has cerebral palsy but, despite being given an opt-out, was determined to run. He comes in last by a matter of minutes but is flanked by a crowd of cheering classmates.

This led to a discussion on what it means to fail. Students came up with some amazing definitions, including: “Failure is when you don’t even try, because you are afraid of not achieving your goal.”

Again involving tutors, students were given a seven-day “Epic Fails” diary, and asked to record a failure a day and think about how they could respond to it positively.

Then the gorilla arrived. In Year 9, students are often on the receiving end of a huge amount of feedback leading up to GCSE option choices, at an age when they can be particularly sensitive to criticism. Dweck’s research showed that students with a fixed mindset tended not to engage with feedback as actively as those with a growth mindset.

This is completely logical: if you don’t believe you can improve, why waste the time listening? So, the challenge is to persuade students to attend to pointers on how to improve rather than be too distracted by headline grades or comments, which may reinforce a fixed mindset.

I had come across Simons’ and Chabris’ 1999 selective attention test online, and tried using it as an activity to show students that you tend to see only what you are looking for - I won’t say too much; have a go yourself (bit.ly/AttentionTest).

We then looked at ways of responding to feedback and helping students to realise that they have a choice, not just about which GCSEs to study but also about how they react to life’s ups and downs, in academic performance and also in their extracurricular activities, and even in their relationships.

Into the learning pit

As we developed the programme, it became increasingly clear that students’ feelings were playing a highly influential role in this growth mindset work. While the principles could quickly be explained, students also needed to understand their own emotions as they tried to choose helpful responses to challenge and failure. Increasing students’ emotional “granularity” - their ability to identify, distinguish between and name a wide variety of feelings - was added to our aims.

In the “Epic Fails” diary, we inserted a column for recording emotions attached to a particular instance of failure, and provided and discussed a glossary of emotions to support students in expanding their range. Their ideas on growth-mindset responses to failure instantly multiplied.

For example, a student who had taken the time to register that she’d felt a little humiliated, left out and bored when she wasn’t invited to a party suddenly felt more able to think of constructive ways of bouncing back (“I’ll arrange to meet someone I don’t know so well yet; I’ll be able to finish my computing project”) than if she had just tried to grit her teeth and forge ahead regardless.

Meanwhile, alongside the year groups’ programme, several departments had come forward with particular issues in their own subjects. There was a perfectionist group of girls in a humanities band who were loath to take risks with their thinking and writing; the art department wanted to see more freedom and risk-taking with media; and the maths department had students who felt the “Not a mathematician” label applied to them. Each department had ideas about how to apply our four growth-mindset principles in their areas.

A religious studies teacher deliberately gave students the wrong task to do, then, after a few minutes, led a searching discussion on why we find it difficult to get things wrong and just cross work out and start again. In maths, students were encouraged to self-assess how willing they had been to persist with problems, and there were displays of “work in progress” and interesting errors rather than the finished product.

We ran staff training sessions on growth mindset in practice. In a flat-pack challenge, staff teams built furniture, with the added complication (and hilarity) of missing instructions and a few blindfolds.

A member of each team observed and contributed to live threads via our virtual learning environment, discussing the reactions and strategies of the team.

We followed up with some input on James Nottingham’s concept of the “learning pit” (bit.ly/LearningPit_explained), and how we can encourage students to engage with challenge as well as modelling it ourselves.

We agreed to extend this to peer observations on the theme of “struggle time”, when we would give students more opportunities to get into the “pit”.

Knowing where to stop

As you are beginning to see, when you start embedding growth mindset, it can be tricky to know where to stop.

For example, some of the literature warns against setting and grading; indeed one of Hattie’s top “effect sizes” (a simple measure for quantifying the difference between two groups or the same group over time) is connected to teacher perceptions of students’ potential. If we think they can’t, then maybe they won’t. On the other hand, many teachers feel they can teach more focused lessons if there is some ability grouping.

We have retained setting in some subjects but have made tweaks in other areas to try to avoid labelling students and inadvertently fostering limiting mindsets. For example, we no longer use the term “gifted and talented”, although we do provide stretching and monitoring for students who show outstanding levels of commitment and curiosity.

We have no “grade” terminology, in order to direct the students’ attention to comments and corrections rather than judgements.

We have report-writing guidelines that avoid terms such as “talented”, “flair” and “potential” and which, instead, emphasise behaviours that can be deliberately cultivated, such as effort, persistence and willingness to be wrong.

We have included comments on character development in our lesson planning and observation forms, giving it equal status to differentiation and progress.

It is an organic process of evolution, not just of our PSHE programme but of the whole experience of school.

Character development is difficult to quantify, partly because some of the fruits of a programme will only be tasted in the much longer term. We are glad our students have developed resilience so that they can persevere with their design and technology project when the going gets tough, but we also hope they will use resilience later in life when they have a difficult boss, or they simply find it a challenge to work out the full implications of their mortgage terms.

However, we have had some encouraging feedback in the medium term. Last year’s visit from the Independent Schools Inspectorate saw enough evidence to make the following comment: “Throughout the school, pupils are unafraid of being wrong, not judging this as failure but as a new learning opportunity.

“They react positively to challenges and occasional setbacks, and thus develop excellent confidence and strong resilience, which enables them to respond successfully to the choices open to them at the different key stages of their educational development.”

But my personal favourite feedback is a photo I keep pinned above my desk. It is an image of our head of German riding a tandem on the exchange last year with a girl who said she absolutely couldn’t ride a bike. He corrected her, saying she just couldn’t ride one yet. And a three-hour ride along the Trave river proved him right. When growth mindset moves from theory through practice to instinct, our students will achieve more than any of us dream of.

Gail Haythorne is a senior teacher at Woldingham School, Surrey

This article originally appeared in the 26 April 2019 issue under the headline “Not just a mindset but a way of life”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters